Knowledge that lasts: Repurposing farmer-led extension models in Benin

Testing farmer-led knowledge sharing approaches for strengthening sustainable land management and climate resilience in Benin

by Check Abdel Kader Baba and Wangu Mwangi | 2020-12-04

They are akin to monuments of failure. The rusting water pipes, crumbling roads, abandoned factories, and other remnants of long-forgotten projects that dot the “development landscape” in many African countries. But unrealised development dreams are not limited to bricks and mortar. Many development initiatives also fall short of their goals of disseminating the amassed knowledge and skills beyond the initial (externally funded) project phase.

TMG Research, in collaboration with GIZ soil rehabilitation project (ProSOL) in Benin, recently coordinated a project to test farmer-led knowledge sharing approaches for strengthening sustainable land management and climate resilience in Benin. Concerned about the low diffusion of sustainable agriculture practices promoted by various development initiatives in the past, the project started off with a pilot in two villages to examine the root causes of the problem. Among other findings, the research team found that various sociocultural constraints prevented the effective flow of knowledge from ProSOL-trained farmers — who had also been tasked with hosting demonstration plots — to other farmers. This in turn had contributed to mistrust among community members, resulting in a lack of local ownership, which is crucial in bringing more farmers on board in order to achieve real impact.

In collaboration with ProSOL, TMG Research developed a variant of the farmer-led extension approach to address this gap. The model builds on the concept of “social debt” as it is applied by a network of farmer trainers known as Tem Sesiabun Gorado (TSG), which literally translates as “messenger of the restoration of degraded soils” in the local Baatonou language.

A Tem Sesiabun Gorado training fellow farmers in the hamlet of Koussounin, Kabanou village

Based on insights gleaned from testing the TSG approach in the two pilot villages, TMG has published a technical guide: The Tem Sesiabun Gorado Model: A farmer-led knowledge diffusion approach to promote sustainable agriculture in northern Benin that outlines key principles for designing, implementing, scaling out, and sustaining locally-led knowledge projects.

Motivation and accountability: Missing links in conventional knowledge-sharing models

Over the years, diverse studies have found that most bottom-up agricultural extension approaches — including those that build on farmer-to-farmer knowledge sharing — fail to achieve impact¹.

Ironically, this challenge is faced both by projects that do not remunerate farmer trainers (leading to poor motivation), as well as those that do (due to problems with sustaining commitment once project funds run out). One of the underlying issues is that projects often underestimate the heavy workload for farmers tasked with promoting agricultural practices. An associated challenge is that many extension programmes do not establish oversight mechanisms at the local level to hold lead farmers (and other knowledge workers) accountable to the community.

Moving from individual to social accountability: The principle of “social debt”

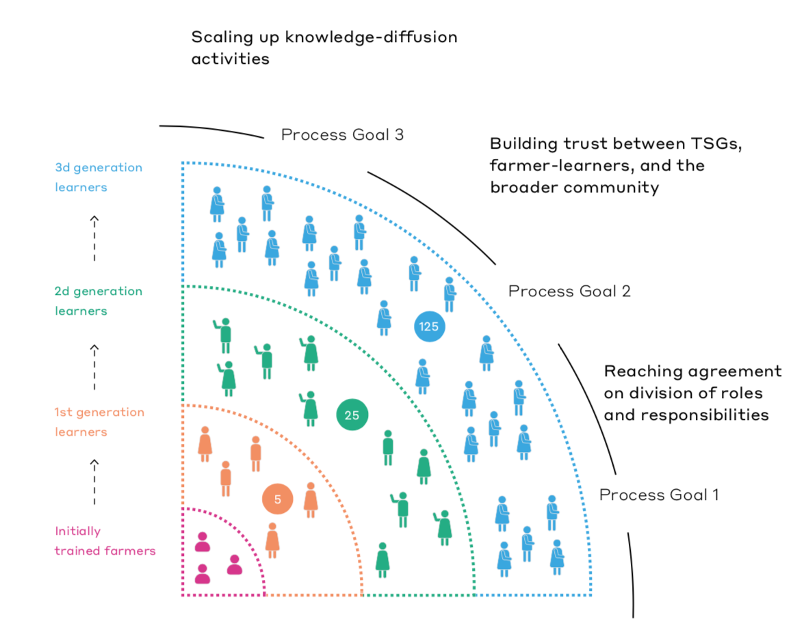

Building on these insights, the TSG model is designed as a cyclical mechanism that can stimulate the dissemination of knowledge and skills from one “generation” of trained farmers to the next. The model’s nine steps cover, among others: initial diagnosis of knowledge gaps at community level; systematic training and follow-up of a core group of (community-endorsed) farmer trainers; and establishing community governance mechanisms to hold trained farmers accountable.

Logical framework of the TSG model

Rather than offering financial incentives to individual farmer trainers, the model seeks to build collective ownership of, and accountability for, the knowledge-diffusion process, and hence ensure its sustainability in the long term. Such communal ownership is propagated in several ways. First the project makes efforts to mobilise a broad cross-section of the community during the early phase of the project. The initial TSGs (farmer trainers) are nominated by fellow villagers at public meetings, where their responsibility for sharing the knowledge learnt with their peers is emphasised. This “social debt” becomes a mechanism for individual and collective accountability that serves as the basis for the sustainable transfer of knowledge and skills between farmers participating in a development project, and those in the broader community.

A concrete example of this principle is the linking of knowledge dissemination to access to seed inputs. In standard agricultural extension projects, free seeds are usually reserved for trained farmers, or those hosting demonstration plots. By contrast, the TSG model stimulates farmer trainers to repay their social debt by not only sharing the knowledge gained, but also “giving back” some of the seed received from the project that they have subsequently multiplied on their own farms.

In this way, successive generations of farmer-learners are not only able to obtain knowledge, but also to build up their own stock for coming years.

A certificate awarded to the first generation of TSGs

Some early lessons

Based on the promising results from the pilot project, ProSOL has adopted the approach as part of its strategy to expand sustainable land management practices in over 400 villages, spread across 18 municipalities in the country. If fully adopted, these farmer-managed practices are expected to contribute to the rehabilitation of approximately 200,000 hectares of degraded land.

While one TSG “graduation” is insufficient indicator of long-term change, some valuable lessons have been learnt that could help enhance the chance that the TSG model will fare better than comparable approaches.

1. It is critical to embed the TSG model within a broader social support, and accountability structure: The degree to which TSGs are embedded within their communities is a critical factor in sustaining local ownership, as well as accountability mechanisms. The TSG model strives to attain a balance between motivating individual community change agents, while keeping them accountable to the broader community. This is a delicate balancing act that requires trust. One of the ways that the TSG model does this is giving TSGs the autonomy to select their mentees from among their own social networks.

2. Building autonomous community knowledge infrastructure requires redefining the support role of extension agents: At its heart, the TSG model entails a paradigm shift in the way that development projects and programmes promote sustainable agriculture practices. In addition to passing on information and skills to farmers, technical advisers are increasingly called upon to contribute to an enabling environment in which farmers can share the results of their experimentation with their peers. This necessitates (re)training of extension agents to understand, and respect, demand-driven approaches to knowledge.

3. Development institutions and partners need to listen better: Institutional learning is a slow process. But as highlighted by the TSG pilot, to truly empower community-led processes, higher-level actors, including government departments, development partners, and NGOs, may need to adapt some of their approaches to providing capacity development support.

The west African region has a rich history of griot singer-poets who have successfully passed on knowledge from one generation to the next. Moreover, social media, and other modern information-sharing tools are not only increasingly ubiquitous, but affordable. By exploring ways to marry age-old wisdom with modern communication channels, perhaps the TSG can offer, as hoped for in the Guide, “… an alternative pathway to counter the high dropout rates associated with conventional farmer-to-farmer extension approaches.”

[1] Franzel et al., 2019; Nakano et al., 2018; Simpson et al., 2015; Ssemakula and Mutimba, 2011

About the project

The TSG model in Benin has been developed and piloted by TMG Research as part of the Global Initiative One World No Hunger financed by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). All publications, including short films of this research project can be accessed here: https://soilmates.org/

The idea of this accompanying research project was born at the Global Soil Week, a platform bringing together a diverse range of actors to initiate and strengthen policies and actions on sustainable soil management and responsible land governance. The results of the accompanying research project were regularly discussed at the Global Soil Week and provided lessons learnt for a broad range of stakeholders from the partner countries and beyond. More information can be found here: https://globalsoilweek.org/

Urban Food FuturesFeb 09, 2026

Urban Food FuturesFeb 09, 2026Pushing the horizon: Urban farming and community-led innovation in Mukuru informal settlement

A small community-run greenhouse in Mukuru is offering insights into how controlled-environment agriculture can strengthen food security in urban environments under increasing pressure—and a look into the future of food systems in informal settlements.

Christian Sonntag, Emmanuel Atamba, Lumi Youm

Land GovernanceDec 18, 2025

Land GovernanceDec 18, 2025Land tenure, women’s land rights, and resilience: Reflections from CRIC23 toward UNCCD COP17

Our experts discuss what the exchanges at CRIC23 highlighted and revealed about the role of secure and gender-equitable land tenure in the UNCCD's work ahead of the 2026 triple COP year.

Frederike Klümper, Washe Kazungu

Urban Food FuturesDec 09, 2025

Urban Food FuturesDec 09, 2025The story of Mukuru's Urban Nutrition Hub

In Mukuru informal settlement, a safe haven for women has grown into the Urban Nutrition Hub, a multi-purpose space for nutrition education, training, and community development, demonstrating the potential of grassroots community-owned innovation..

Serah Kiragu-Wissler

Written by Check Abdel Kader Baba and Wangu Mwangi